Optimal Payment Sequence (Supplement)

Allen Sirolly / September 16, 2017

This post is a supplement to Calculating Returns for Two Kinds of Servicing Fee Schemes.

In the previous post I explored the question of why an investor in Lending Club loans may desire early payment by the borrower, conditional on how servicing fees are levied as well as on the sequence of payments . I assumed a couple of “simple” instances of to make my case, but it’s easy to imagine the more general question of what the best an investor could hope for, given , might be. From an investing standpoint, this isn’t really a useful question to ask—after all, investors don’t get to choose how the borrower repays. But it sounds like it might be an interesting math problem, so why not?

Formally, given we’d like to know what sequence of payments maximizes the investor’s (nominal) IRR, where principal amortizes according to In addition, there are constraints and for , where is the installment

For the last period, all we need is for the borrower to pay down the remaining principal, i.e., , even if . To make the problem a bit simpler, let’s tack on an explicit constraint for some small amount —say, $1—instead of allowing to be arbitrarily small.

With respect to investor fees, let’s consider since it’s suggestive of a dynamic tradeoff between fees and interest: on the one hand, the investor would like the principal to amortize quickly to decrease fees, but on the other hand would like it to remain high to earn more interest. The objective, then, is to maximize satisfying

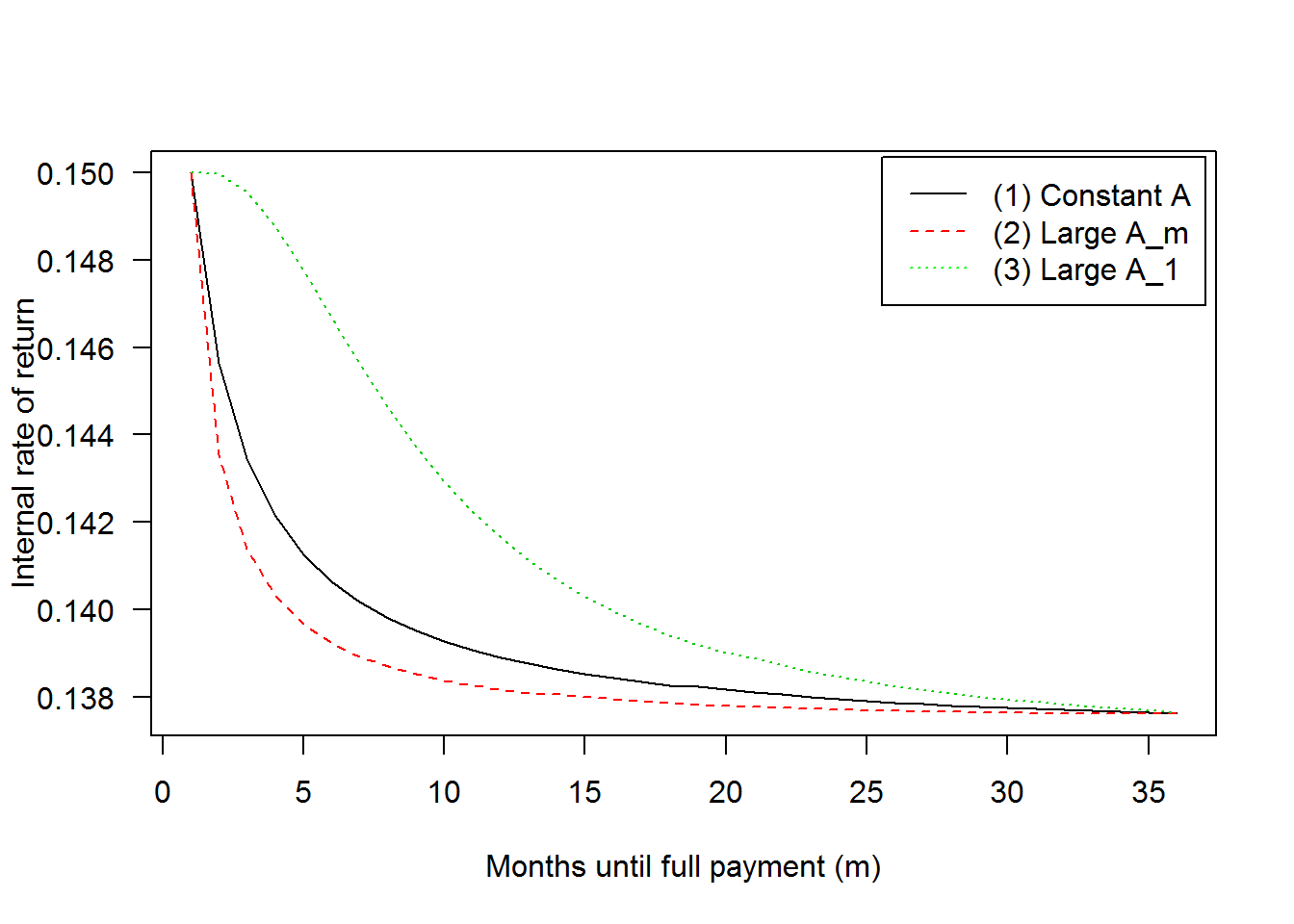

I already considered two possibilities in the previous post: (1) constant payments and (2) installments followed by a large . Before trying to find the optimal sequence, let’s take a look at the possibility of (3) a large followed by the minimum allowable payments in the remaining periods. For the initial payment can be calculated by first considering a “simpler” sequence of large followed by installments. needs to be such that can be paid down in exactly installments, i.e., Then (after some algebra) and . We can then transfer of payment to at rate , so that (If this isn’t apparent, read on for an explanation.)

We can reuse the functions from the previous post, modifying gen_A_seq accordingly:

A = function(P0, r, m) {

# P0 -- initial principal

# r -- interest rate (monthly)

# m -- number of payment periods

P0 * r * (1 + r)^m / ((1 + r)^m - 1)

}

P_i = Vectorize(

# Compute outstanding principal after i payments

function(A_seq, P0, r, i) {

# A_seq -- sequence of payments (length m)

if (i==0) return(P0)

(1 + r)^i * P0 - sum(A_seq[1:i] * (1 + r)^((i-1):0))

},

vectorize.args = 'i')

gen_A_seq = function(P0, r, m, Term=36, k) {

# k -- switch number

switch(

k, {

# 1 -- Constant payments

rep(A(P0, r, m), m)

}, {

# 2 -- m - 1 installments followed by large A_m

Inst = A(P0, r, Term)

A_seq = rep(Inst, m - 1)

c(A_seq, (1 + r) * P_i(A_seq, P0, r, m - 1))

}, {

# 3 -- Large A_1, if (m > 1) m - 2 installments, A_m = 1

if (m==1) return((1 + r) * P0)

Inst = A(P0, r, Term)

P1 = P0 * ((1 + r)^Term - (1 + r)^(Term - m + 1)) / ((1 + r)^Term - 1)

A1 = (1 + r)*P0 - P1 + (Inst - 1) / (1 + r)^(m-1)

c(A1, rep(Inst, m - 2), 1)

}

)

}

R1 = Vectorize(

function(s, P0, r, m, k) {

# s -- service fee rate (monthly, on remaining principal)

# P0, r, m -- args to A()

# k -- switch number (payment sequence 1, 2, or 3)

A_seq = gen_A_seq(P0, r, m, k=k)

fun = function(z) (P0 - sum((1 + z/12)^-(1:m) *

(A_seq - s * P_i(A_seq, P0, r, 1:m))))^2

# solve for IRR

optimize(fun, interval=c(0, .5))$minimum

},

vectorize.args = 'm')Also keeping with the previous post, let’s make the test case a loan with $1000 principal and 15% annual interest rate, with service fee rate equal to 1.3% per annum.

# Compute the IRR for each m, for each sequence -- 36 x 3 matrix

IRR = sapply(1:3, function(k) R1(s=.013/12, P0=1000, r=.15/12, m=1:36, k))

matplot(1:36, IRR, las=1, type='l',

xlab='Months until full payment (m)',

ylab='Internal rate of return')

legend('topright', c('(1) Constant A', '(2) Large A_m', '(3) Large A_1'),

lty=1:3, col=c('black','red','green'), inset=.01)

Sequence (3) is rather extreme in that payment is front-loaded as much as possible without violating any of the constraints. As it turns out, it is also optimal. To prove it, I’ll use (3) as a starting point and show that moving part of payment downstream to (the only permissible action since only is not already bound by a constraint) cannot increase . Since any permissible (given ) can be constructed starting from (3) and redistributing payment from , it will follow that (3) must be the optimal sequence.

Let me first introduce the notation to describe the marginal change in from transferring a marginal amount of to , holding all other payments fixed, and in such a way that the constraint remains satisfied. (More conventionally, this can be thought of as a directional derivative , where is an -dimensional unit vector with non-zero components and .1) The claim, then, is that for all .

Importantly, cannot be 1:1 due to compounding. In particular, while , This ensures that remains unchanged, and therefore that the remaining payments still lead to . (To avoid ambiguity, define when .)2

Calculating is a little bit tricky because is defined implicitly in the objective function; we’ll need to use implicit differentiation. Taking derivatives of both sides of the objective function (defining to simplify notation) and rearranging yields (See here for a step-by-step derivation.) Assuming that is not too large so that the denominator is positive, when the numerator is non-positive, i.e., when where . Since cannot be higher than the interest rate, , and the above inequality can be rearranged to , which always holds as is assumed to be non-negative. Thus, unconditionally for all , with strict inequality if .

As an exercise, try verifying the following properties: ↩